Summerisland Passive House + August 2018

Summerisland Passive House

Summerisland House in County Armagh is the expression of an idea that has taken shape over the years in the pages of this very magazine: the passive house as an ideal family dwelling. Situated on a rural site just west of Portadown, the plan was to, at once, resemble a traditional cluster of Irish farm buildings, while also offering a contemporary and light-filled living area – all while meeting stringent energy targets.

As a result, some unusual design decisions were taken, with the building taking on a near-cruciform shape, complete with vaulted ceilings and multiple sections. The payoff is that the house somewhat differs from the traditional passive house form. It’s much easier to meet the standard with simpler shapes, fewer tricky junctions to insulate and seal, and as little surface area as possible through which heat can escape. The house’s designer Paul McAlister, principal at Paul McAlister Architects in Portadown, County Armagh, says that one of the main goals was to match an elegant modern design with the low energy demand of a passive house.

“We hope it’s a nice elegant house and an attractive piece of architecture that also has low energy performance,” he says. When it came to the design — high ceilings and a mixture of the old and new — inspiration came from close to home: the roof forms in particular, with their change in eaves heights, are reminiscent of a traditional rural cluster.

“The concept of the design was the layout of traditional farmhouse buildings. Our practice is in the countryside; I’m from a farm myself,” says McAlister. “I like to have houses within the reach of ordinary people.”

Designed with wheelchair accessibility in mind, almost everything is on the ground floor, with only guest bedrooms on the first floor. Glazing – consisting of large expanses of high performance Internorm triple glazed windows and doors – is positioned to the east, south and west side of the main living area.

“In the main kitchen-dining-living space, it gives you a lovely vaulted feeling. You get the notion that it’s a rural cluster of barns, and yet it’s contemporary,” he says. Summerisland is McAlister’s second fully-certified passive dwelling – though his 455 sqm home for The Centre for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technologies (CREST) at South West College in Enniskillen was also certified – but in this case the idea of a passive house case came as much from the client as from the architect.

Nonetheless, McAlister is a veteran of the passive house movement at this stage — he was the first person in Northern Ireland to become a certified passive house designer back in 2010. “I was personally very interested in it, maybe for techy, anorak reasons, but there was no demand for it back then.” But that has started to change, as his growing practice bears out.

“The passive house system relies on five elements: insulation, airtightness – which is the most difficult thing for a builder to achieve on-site – high quality windows and doors, thermal bridge detailing of the elements, and ventilation, in this case with heat recovery,” he says.

“The client came specifically to us looking for a passive house. It was my second certified one, and we’ve just finished another, and done a [passive standard] school. It’s the first passive certified education building in Northern Ireland. We’ve also done another five [dwellings] that would meet the certification,” he says. Asked how he came to design a house

that is out of step, in terms of building form, with what we traditionally conceive of as a passive house, McAlister says that there is no reason to avoid aesthetic experimentation if the technical side of the design and construction is properly carried out. The demand for a house that conserves energy does not necessarily require a simple cuboid shape.

“My personal view is, within reason, you design the house you want—south-facing windows help obviously, but people want those anyway. Nearly any building can be made passive, even north-facing ones, which is something that people [often] don’t appreciate.”

Summerisland’s blockwork construction is another interesting factor. The build method here is about as conventional as it could possibly be: cavity wall construction sitting on a strip foundation. Wall insulation is full-fill polystyrene bead with boards used only in the floor and ceiling. “It’s a traditional block with a very wide cavity,” says McAlister. “The solidity of the thing is quite nice, and you have good sound-deadening between rooms. It also has a small advantage in terms of thermal mass.”

It’s a case of horses for courses, he says. “Sometimes you get a client who has a serious ecological bent who only wants natural materials, and sometimes they are concerned more with performance.” Having been elected in 2017 as chairman of the Passive House Association of Ireland, McAlister is also interim co-chairman of nZEB Ireland, a new independent body set up to help ensure that Ireland doesn’t fall short in implementing the EU’s mandated nearly zero energy building standard. So, it was befitting that McAlister commissioned BER assessors IHER to check how Summerisland fared relative to Ireland’s proposed nZEB definition, even though it will not apply in Northern Ireland. The house blitzed the requirement, reaching an Energy Performance Coefficient of 0.138 – an 86.2% energy reduction on the 2005 build specs that Ireland’s regs use as a benchmark. The calculations also show the house achieving an A1 building energy rating under the Republic’s rating system. McAlister seems pleased with the result, seeing it as a vindication of the high quality of the design. “nZEB will be mandatory for all new homes from 1 January 2020 in the Republic of Ireland.

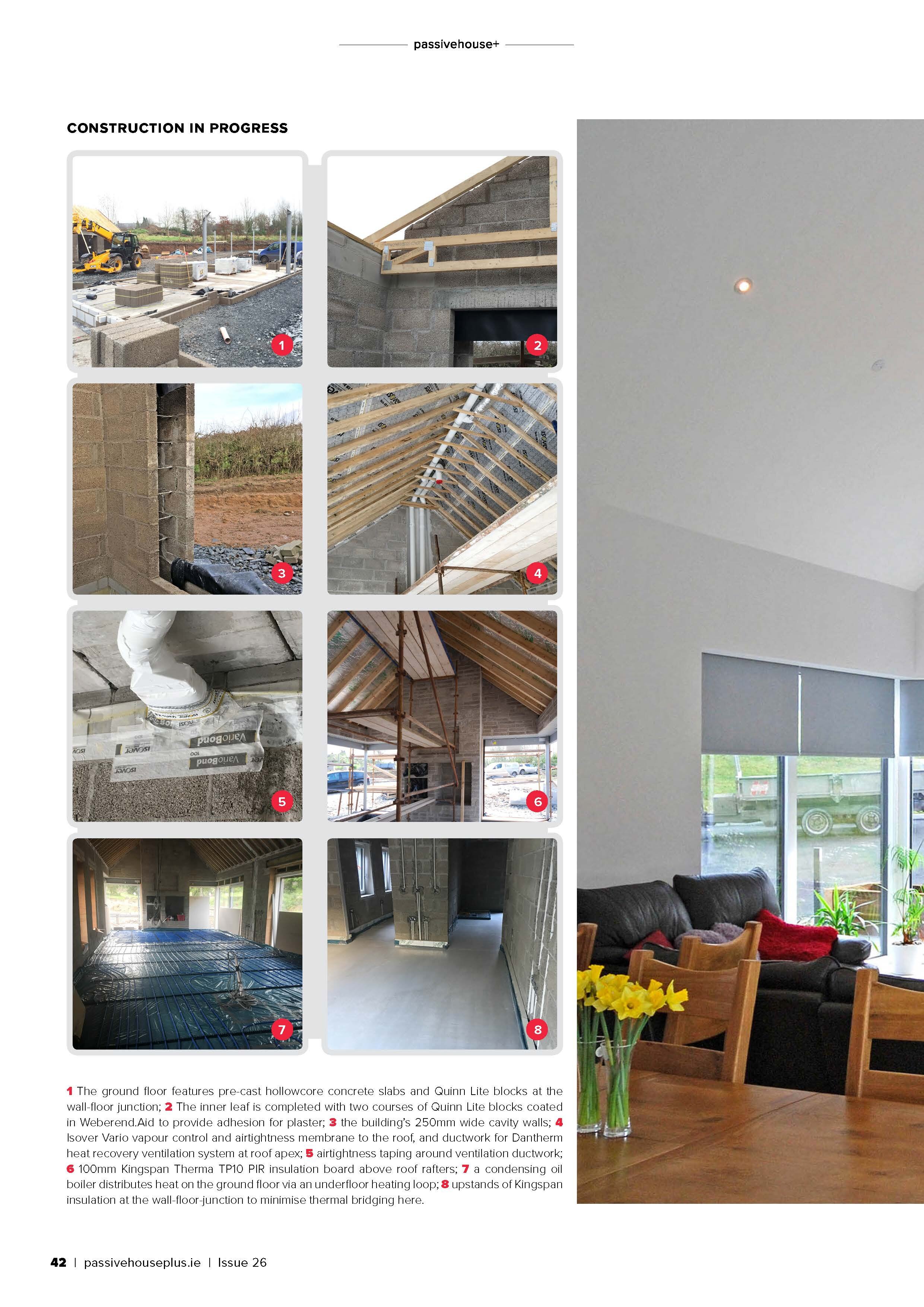

In order to achieve it you need, basically, a passive house, plus some component of renewables.” While the original plan was to install an air source heat pump at Summerisland, that would have necessitated the installation of a new transformer on the local electricity network, a fairly costly upgrade. So, a condensing oil boiler was chosen instead, which distributes heat on the ground floor only via an underfloor heating loop. There’s also a 4kW solar photovoltaic array. McAlister is satisfied the oil will rarely need to be turned on. “The oil-fired burner was the smallest on the market,” he says.